This here will be about how American and British interest we’re in the draconian Apartheid regime in South Africa in 1970s and 1980s. I been looking into how businesses at the time went through hoops and not caring about the United Nations Sanctions and resolution 418 of 4th November 1977 states this:

“Determines, having regard to the policies and acts of the South African Government, that the acquisition by South Africa of arms and related material constitutes, a threat to the maintenance of international peace and security; Decides that all States shall cease forthwith any provisions to South Africa of arms and related materiel of all types, including the sale of transfer of weapons and ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, para military police equipment, and spare parts for the aforementioned, and shall cease as well the provision of all types of equipment and supplies and grants of licensing arrangements for the manufacture of the aforementioned” (UN, 1977).

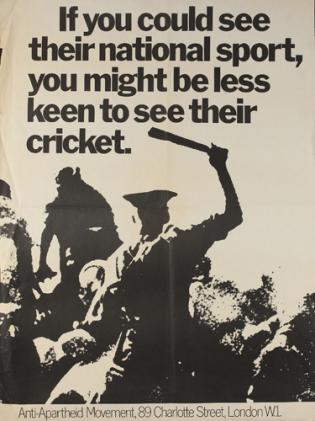

So with that in mind, we can see how businesses of United States and Britain started and worked as subsidiaries in South Africa during the Apartheid, where the instances of FORD Motors and Leyland Vehicles we’re produced and used by the Police under the worst atrocities of a regime who used their laws, security agencies to harass the majority; while keeping the minority rulers and their economic incentive intact by any means. So that big business and other ones defied the Sanctions and even collaborated with necessary arms, cars and other procurement for the totalitarian state; shows how far the Corporation goes for profit and serve even governments who has no quarrel with prosecuting innocent citizens. Therefore the history of these corporations and their dealings should come to light and be questioned. As business today does the same under regimes that are totalitarian and militaristic with the favor of elite and harassing the opposition. That is why we can see at the tactics of the 1970s and 1980s and see how they might be used today.

So with that introduction take a look at my findings and hope you find it interesting.

How to start the discussion:

“Johannesburg Star (South African daily), Nov. 26, 1977, at 15. See also 1978 Hearings, supra note 13, at 846 (statement of John Gaetsewe, General Secretary of the banned South African Congress of Trade Unions) (“The ending of foreign investment in South Africa … is a means of undermining the power of the apartheid regime. Foreign investment is a pillar of the whole system which maintains the virtual slavery of the Black workers in South Africa.”); Christian Sci. Monitor, Feb. 21, 1984, at 25 (statement by Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela)” (Hopkins, 1985).

Some money earned by the SADF at the time:

“According to official SADF accounts, the money that would have been recouped from the sale of ivory would flow back into funding the Unita rebels. However, Breytenbach knew that in the year 1986/1987 alone, the SADF’s assistance to Unita through military intelligence totalled R400 million (ZAR2005=R2,5 billion) and this excluded the supply of almost all Unita’s hardware and fuel. It is therefore unlikely that this was the reason behind the SADF’s interest in ivory smuggling. It is more likely that the potential for self-enrichment that this presented to SADF officers was enormous. General Chris Thirion, Former Deputy Chief of Staff Intelligence, agrees and suspects that Savimbi was in fact over-funded at the time” (Van Vuren, 2006).

How much RSA used on Military Equipment during Apartheid in the 1980s:

“According to evidence presented to the UN Security Council arms embargo committee in 1984, out of its annual total arms procurement budget of some R1.62 billion over R900 million was to be spent on arms purchases from overseas” (…)”This R900 million is spent on the procurement of arms directly by the regime from overseas and via the private sector. No official figures are published about how much is actually spent on direct imports of armaments. However, it can be estimated from figures contained in an in-depth survey by the Johannesburg Sunday Times in July 1982 that imports from overseas were 15 per cent of defence spending which then stood at R3,320 million per annum” (AAM, 1985).

How that happen:

“Those breaches of the arms embargo which have been exposed have also revealed the myth of South Africa’s self-sufficiency. Equipment smuggled into South Africa include weapons such as machine guns, rifles and pistols as well as spares and components for them. In a trial at the Old Bailey, London, in October 1982, the Court was informed that South African efforts to produce components for pre-war machine guns had not been successful. This points to the serious deficiencies in the quality and reliability of even minor items manufactured in South Africa” (AAM, 1985).

Export of R.J. Electronics International:

“Britain’s refusal to strictly implement the UN arms embargo and its continuing military collaboration in various fields are not totally surprising since much of this arises out of its traditional relationship with South Africa” (…)”They failed to re-appear in Court on 22 October 1984 and the following weekend gave a press conference. At it, Colonel Botha disclosed that they had operated as undercover agents for five years and “had saved the country at least R5 million on purchases of vital equipment”. Metelerkamp claimed he was only a consultant to Kentron and was the Managing Director of R J Electronics International. However, it emerged that he had been employed by Kentron up to a month prior to his arrest, and R J Electronics International was “a company used to purchase illicit arms” (AAM, 1985).

Other Examples:

“One cargo of FN rifles was initially exported by air to Red Baron Ltd at an address in Zurich before being forwarded to South Africa. This company, however, was not Swiss, but registered in England. Its directors were Mr Trinkler and two others who had also been directors of Kuehne and Nagel in Britain” (…)”The most controversial case was that of the British Aerospace naval reconaissance aircraft, the Coastguarder. In Hay 1984 it was disclosed that British Aerospace had been approached by the South African Government and that initial discussions had taken place concerning the purchase of eight aircraft. These were to replace the Shackleton aircraft which were having to be phased out. The South African authorities had sought to evade the arms embargo by forming a Coastguard service as a civilian authority through which the order for the aircraft would be placed. Repeated efforts to secure from the Government an undertaking that the Coastguarder would not be granted licence for export to South Africa met with the response that “it would not be proper for me to offer a definitive view now on the hypothetical question on the issue of a licence for the export of an aircraft such as the Coastguarder to South Africa” (AAM, 1985).

Shell Corporation working with the Regime:

“The South Africans agreed and supplied a cash advance that allowed the traders to purchase a tanker, shipping company and the required insurance. The tanker docked in Kuwait and filled its tanks with oil owned by Shell. The oil was registered for delivery in France. However, en route to Europe from the Gulf the tanker stopped in Durban and off-loaded almost all of its oil crude oil—almost 180,000 tonnes—with the South Africans paying the difference between the purchase price and the fees it had advanced for the purchase of the tanker. The Salem was then filled up with water in order to create the impression that it was still laden with oil. Off the coast of West Africa (Senegal), at one of the deepest points of the Atlantic, the ship was scuttled and the crew, who were prepared for the evacuation, were conveniently ‘rescued’. They had hoped to make an extra $24 million off the insurance claim for the lost oil. Following investigations by the insurance company the main perpetrators were prosecuted. The biggest loser next to Shell was South Africa, asit agreed to pay the Dutch multinational US$30 million (ZAR2005=R436 million) in an out-of-court settlement. Shell was left to carry a remaining loss of US$20 million. The use of corrupt middlemen had cost South Africa almost half a billion rand. There was no prosecution in South Africa of the officials at the SFF who had authorised South Africa’s procurement of a full tanker of oil from three novice (criminal) entrepreneurs” (Van Vuren, 2006).

British Subsidiaries in South Africa:

“Many of these subsidiaries are British. They include Leyland (Landrovers and Trucks); ICI (through its 40 per cent holding in AECI) (Ammunition and Explosives); Trafalgar House (through Cementation Engineering) (artillery shells); ICL (Computers); GEC including Marconis (Military Communications Equipment); Lontho (aircraft franchises); Plessey (Military Communications Equipment); BP and Shell (oil and other petroleum products for the military and police)” (…)”An impression of the full extent of the role of British subsidiaries in South Africa in undermining the arms embargo can be obtained from studying Appendix C. This is a list of British companies with subsidiaries in South Africa which are also known to be engaged in the manufacture of military and related equipment” (AAM, 1985).

British Mercenaries:

“British mercenaries, some recruited. originally for the forces of the illegal Smith regime, are serving in a number of South African Defence Force units, including the infamous “32 Battallion” operating out of Namibia into Angola. A British mercenary was killed in the South African commando raid on the residence of South African refugees in Maputo, Mozambique, in January 1981” (AAM, 1985).

“British Government policy so far has been to grant permission for Officers to serve in the South African Defence Forces.” (…)”This was explained by Secretary of State for Defence, Michael Heseltine, in a letter to the Rt Hon Denis Healey:

“An Officer is required to resign his commission before joining the forces of a country that does not owe allegiance to the Crown, and if he did not do so then the commission would be removed. As you will appreciate, this is the only power that we can exercise over an officer who has already retired from the Services. Guidance is given to officers about these procedures before they retire, but no specific recommendations are made about which countries’ Armed Forces an officer should join; nor do I believe that it would be right to do so.” (AAM, 1985).

American Businesses under Apartheid:

“Approximately 350 of the most prominent companies in the United States, including more than half of the Fortune 500’s top one hundred firms, operate subsidiaries in South Africa [18]. Another 6000 do business there through sales agents and distributers [19]. The United States holds fifty-seven percent of all foreign holdings on the Johannesburg stock exchange, including gold mines, mining houses, platinum mines, and diamonds [20]. The State Department estimated that U.S. direct investment amounted to $2.3 billion in 1983, down from the $2.8 billion calculated by the South African Institute of Race Relations for 1982 [21]. Other estimates put overall American investment, including loans and gold stocks, at $14 billion [22]” (…)”rcent [25]. U.S. exports to South Africa, however, grew from approximately R1.2 billion in 1979 to R2.7 billion in 1981 [26]. As a result, the United States emerged as the Republic’s largest trading partner [27]. Apart from its quantitative impact, U.S. business investment has a qualitative impact disproportionate to its financial value” (…)”John Purcell of Goodyear concurred, asserting that economic pressures will not encourage nonviolent social change in South Africa; rather, this will be brought about by “economic growth, expanded contact with the outside, and time” ((Hopkins, 1985)

Ford sold cars to the Apartheid regime:

“Ford Directed and Controlled its South African Policies from the United States, Exported Equipment from the United States, and Acted to Circumvent the United States Sanctions Regime: (New York Southern Cout Case, P: 65, 2014)

“Thus, despite the tightening of U.S. trade sanctions in February 1978, Ford U.S. still announced a “large infusion[] of capital into its South African subsidiary. Ford injected $8 million for upkeep and retooling” (New York Southern Court Case, P: 67, 2014).

“Ford support was significant: “[B]etween 1973 and 1977 [Ford] sold 128 cars and 683 trucks directly to the South African Ministry of Defense and 646 cars and 1,473 trucks to the South African police. Ford sold at least 1,582 F series U.S.-origin trucks to the police” (…)”Despite the prohibitions, Ford continued to supply vehicles to the South African security forces with the purpose of facilitating apartheid crimes. Ford denied that its continued sales to the South African security forces ran counter to the U.S. prohibitions, on the basis that the vehicles did not contain parts or technical data of U.S. origin” (…)”Notably, into the 1980s, Ford sold vehicles that did not need to be “converted” by the apartheid government for military or police use but were already specialized before leaving the plant in South Africa” (…)”Ford built a limited number of XR6 model Cortinas known as “interceptors” that were sold almost exclusively to the police. The XR6 was special because it had three Weber model double carburetors, as opposed to all other Cortinas that had only one double carburetor” (…)”Ford knew that the normal market for these vehicles was the security forces. The vehicles were deliberately pre-equipped with armor and military fixtures and designed for easy modification by the security forces to add additional defensive and offensive features” (…)”By making profits which they knew could only come from their encouragement of the security forces’ illicit operations through the sale of vehicles, parts, designs, and services, Ford acquired a stake in the criminal enterprise that was the apartheid regime” (New York Southern Case, P: 71-77, 2014).

Leyland under Apartheid:

“The British government now virtually owns British Leyland and therefore controls the company’s operations in South Africa. Yet it has done little in practice to press for the rights of black workers to organize through trade unions, or for the recognition of the unions for collective bargaining purposes” (…)”The South African “branch” is Leyland’s biggest operation in the world outside of the U.K. At present it is the 8th largest car manufacturer (holding approximately 5% of the market) and the 7th largest commercial vehicle manufacturer (holding approximately 5,5% of the market) in South Africa. Despite the depressed condition of the South African Market it sold 1959 vehicles in January-February of 1977 alone” (…)”B.L.S.A. has massive contracts with the South African state. It is one of the chief suppliers of the South African Defense Force, providing not only trucks and landrovers (which form the backbone of anti-guerrilla operations) but also armored personnel carriers. Of course, the figures for these contracts are never made public” (…)”For example, in June 1976 it was announced that B.L.S.A. had won a £1.9millon order for 250 trucks from the Cape Provincial Authority” (…)”As Leyland itself have argued , It “must conform, it not entirely” to South African government and established wishes” (Coventry Anti-Apartheid, 1977).

This here is not easy to finish up as the implications of this deals and arrangement used to support a government that oppressed and detained the majority. This Apartheid government did it all openly and with a clear message that the white minority should rule, while the rest should serve them.

In that context these businesses earned good amount of cash and profits for their stakeholders and their shareholders. While their products and procured services by the state we’re used to oppress majority of people in South Africa. We can surely see the amount of money and how this have affected the society and given way for the government of the time to continue with the process of detaining and harassing the majority of South Africans. This could not have happen if there wasn’t a helping hand from businesses and their subsidiaries. This here is just a brief look into it.

Certainly this should be studied even more and become clear evidence of how heartbreaking it is to know how certain businesses and people owning them will profit on suffering of fellow human beings. That is why I myself shed a light on it, to show the extent of disobedience of the UN Resolution and also what these corporations does in regimes that harassing and oppressing fellow citizens for their background, creed, tribe etc. It’s just ghastly and makes my tummy vomit. But that is just me, hope you got some indication of how they did their business and served the Apartheid government. Peace.

Reference:

Anti-Apartheid Movement – ‘How Britian Arms Apartheid – A memorandum for presentation to her Majesty’s Government’ (1985)

Coventry Anti-Apartheid Movement – ‘Leyland in Britain and in South Africa’ (1977)

Hopkins, Sheila M. – ‘AN ANALYSIS OF U.S.-SOUTH AFRICAN RELATIONS IN THE 1980s: HAS ENGAGEMENT BEEN CONSTRUCTIVE?’ (1985) – Journal of Comparative Business and Capital Market Law 7 (1985) 89-115, North Holland

United States, New York Southern Court: Case 1:02-md-01499-SAS Document 280-1 Filed 08/08/14

Van Vuren, Hennie – ‘Apartheid grand corruption – Assessing the scale of crimes of profit from 1976 to 1994’ (2006)